Why is Marketplace Revenue so Funky?

Why GMV can be a vanity metric, why the take rate is so important and why contribution margins are so poor

Marketplaces businesses are just different when it comes to revenue. They have super big gross revenues but make very little net revenue. For example, Airbnb reported in their Q1 2022 Shareholder Letter that gross revenue was $17.2B while net revenue was $1.5B.

That means net revenue (called “Revenue” above) was only 8.7% of gross revenue (called “Gross Booking Value” above). On the surface, that seems pretty darn low. Why is that? Does it mean marketplaces are super inefficient businesses? Where does all that revenue go?

This is how marketplaces work, and the waterfall of gross revenue to net revenue is called the take rate (also the name of this newsletter)! I will get to the strict definition of take rate and other metrics below, but this translation of gross to net revenue all comes down to the dynamics of how marketplaces work.

Marketplace Dynamics

Love them or hate them, marketplaces differ from other businesses because they facilitate transactions. Their entire function is to maximize liquidity e.g. the probability that a transaction happens. To do that, marketplaces sit between parties transacting and facilitate swapping goods and services for monetary value (or some other good/service). The more the marketplace is involved in a transaction, typically, the more value they provide for the two transacting parties.

This means the entire transaction volume moves through the marketplace platform, but the platform only keeps a small residual slice of it. The rest of the gross revenue goes to the marketplace’s seller/supply side for providing the good or service. For Airbnb, hosts rent their homes out to guests, which guests pay for. The total booking value e.g. the total amount paid by the guest is the gross revenue. Hosts keep most of that gross revenue, while Airbnb charges a guest fee and takes a percentage of the value from the host. The guests and the hosts share the cost of transacting on the platform. It is the sharing economy, after all. 🤣

Monetization Models

The small slice is typically charged in the form of one of these monetization models:

Percentage Take of the Transaction - Cut of the transaction e.g. keep a flat $ fee or % of the transaction

Platform or Transaction Fee - Additional fee charged to the buyer and/or seller for each transaction

SaaS Subscription - Fees paid for the use of the software for running a business and/or distributing on to the marketplace

Payment Processing Fee - Markup of payment processing fees

Ancillary Services - Paying for liquidity services of some kind e.g. insurance, warranty, protection, legal, etc

Advertising - Paying for exposure to the marketplace audience and/or placement in search

This small slice, aka the take rate, can vary greatly in amount depending on the type of marketplace, value-added, monetization model, industry standards, and many more factors. Now that we have the foundation of the gross revenue to net revenue translation, let's dive into the unique revenue waterfall for marketplaces and the associated margin metrics.

The Marketplace Revenue Waterfall

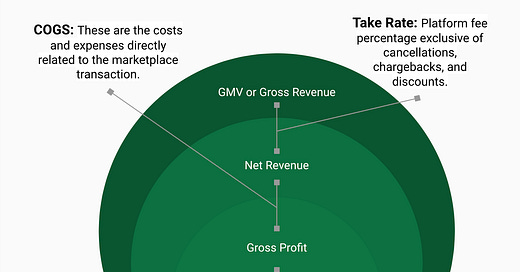

My favorite way of visualizing the revenue pie for marketplaces is the below visual, which shows the waterfall from gross revenue to contribution margin. The latter is the ultimate success metric of a marketplace and whether it will survive in the long run.

Definitions

Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) - Also known as Gross Revenue, is the total revenue produced by the platform by bringing parties together. This has many aliases depending on the industry the marketplace is in. Some of these include Gross Booking Value, Gross Rental Value, Gross Transaction Value, Gross Service Value, Gross Wage Value, Gross Written Premium, and I am sure many more.

Take Rate - Platform fee or other monetization percentages exclusive of cancellations, chargebacks, and platform discounts.

Net Revenue - This is the platform's GMV times the take rate "taken" for facilitating transactions exclusive of cancellations, chargebacks, and discounts.

Cost of Good Sold (COGS) - These costs and expenses are directly related to the marketplace transaction.

Gross Margin - The profit produced off the net revenue less all the COGS e.g. credit card fees, etc.

Variable Expense - All costs associated with a transaction that is not classified as a fixed cost to the business. Some of these costs won’t be genuinely variable such as a yearly SaaS contract for your CRM.

Contribution Margin - The residual profit left to cover all fixed costs after accounting for variable costs. This is typically calculated on a per-product basis.

Benchmarks

As noted in the chart, there are three significant translation moments. Here are all three and the average ranges for them that I typically see:

Gross Revenue → Net Revenue (Take Rate)

B2C - 10-40%

B2B - 1-30%

Net Revenue → Gross Profit (Gross Profit Margin %)

60-80%

Gross Profit → Contribution Margin (Contribution Margin %)

0-40%

Why sometimes GMV can be a vanity metric

The headline metric for many marketplaces is the GMV, mainly because it is the enormous number and the total value of the transactions moving through the platform. The problem is that the GMV can be a vanity metric if the company makes no money from these transactions. The take rate must be sufficient to create net revenue that will lead to a positive contribution margin.

This means a big GMV does not equal big net revenue unless the take rate of the marketplace is sufficiently high. This doesn’t require the actual take rate to be a high number e.g. 25%+, but that certainly helps. The problem with high take rate marketplaces is that they usually have significant friction and lower liquidity hence why the marketplace can charge such a high rate. This tends to restrict the total GMV of these marketplaces, whereas marketplaces with low take rates typically have much larger GMVs.

Low-take rate marketplaces typically are horizontal and/or are B2B marketplaces operating in markets with immense scale. Think of businesses like ACV Auctions (wholesale cars) and Reibus (steel) with massive markets but low take rates compared to their B2C counterparts. In short, the GMV can largely be a vanity metric, and what matters is the underlying dynamics of the take rate and cost structure.

Marketplaces with terrible contribution margins

It is often the case that a marketplace can look great in gross profit margin but have a terrible contribution margin. This is because variable expenses for marketplaces can be a killer, given the high-touch nature of the transactions. Customer support, trust/safety, insurance, and acquisition costs can be massive costs for the business, and the list goes on.

The important part of the revenue waterfall is getting to a contribution margin of > $0. If that is not true, the business will go out of business in the long run without infinite fundraising. Even with a breakeven contribution margin or greater, a platform can lose money due to the fixed expenses of the business. Contribution margins must be sufficiently large, or the business has to have a significant scale to offset these fixed costs.

Note that in the early days of marketplaces, the “variable expenses” are likely more fixed and that as the transaction volume increases, the expenses won’t rise as fast as the net revenue leading to greater gross profit. The main example from above is your CRM costs which have a lower bound on cost but remain somewhat fixed as the business grows. This means marketplaces will initially have poor unit economic metrics but improve over time as they scale and spread variable-ish costs over more transactions.

Calculating gross profit and a thing called float

An important note for gross profit is that startups often calculate it by lumping supply-side payouts and COGs and minus-ing it from GMV. This is a sub-optimal approach, as it is

Not how investors are used to looking at it

Understates the gross profit making it look too low and therefore concerning

It was never truly acquired revenue, so COGs don’t apply.

Where the supply-side payouts can be interesting for revenue purposes is through the creation of financial float and the monetization of it. GMV can be a massive advantage for a business if they collect the total amount and hold it for extended periods e.g. take payment up front and deliver the good or service later as well as the payout later. This reserved cash is called "float," the best part is that it can be used to make money! Typically the float can be used for short-term interest and investments though it needs to be very liquid to cover future payout liabilities. We will dive into this topic in a later post.

Summary

While marketplace revenue differs from SaaS or other businesses, there is a method to the madness. The most important thing to understand is that GMV largely represents the platform’s market penetration and doesn’t dictate how much net revenue the business generates. The net revenue is largely driven by the take rate, which is a function of the platform’s product and offering and the industry standards. So in many ways, GMV can be considered a vanity metric if the underlying unit economics of the business don’t work. For marketplaces, this means ensuring a positive contribution margin on a per-transaction basis in the medium to long term. Successful marketplaces achieve significant contribution margins over time, and the GMV is primarily ignored other than understanding how much market share has been captured.

What marketplace revenue questions do you have? Please leave them in the comments below and I will be sure to address them.

This is such a useful piece - thanks, Colin. I have a question...

Would customer support and developer costs be considered as COGS or variable expense? Or neither?

Great read!

Wondering why you include acquisition costs in the contribution margin when they are closer to fixed expenses rather than variable / COGs? Thanks!